What DO We Do on the Sabbath?

What does keeping the Sabbath look like? The fourth commandment is clear, and numerous other places throughout the Bible make it evident that God finds observation of the Sabbath something all His people should do. Keeping the Sabbath means, in part, refraining from work on that day. We are to refrain from our vocation as well as other work.

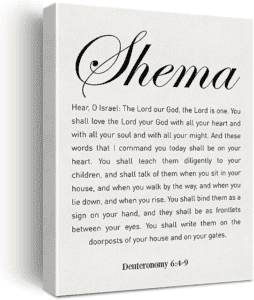

“Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath of the Lord your God; in it you shall not do any work, you or your son or your daughter, your male or your female servant or your cattle or your sojourner who stays with you. For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and made it holy.”

Exodus 20:8-11, (NASB)

What we’re not supposed to do on the Sabbath is clear, but what isn’t exactly clear is what we DO on that day. When we don’t work, do we just lay around and watch TV all day? Should we take a vacation? Run errands? Go to church?

There are several places we can look to find these answers. We can read the Bible and determine what Sabbath observance should look like. For practical application, we can learn from Orthodox Jews, who have been observing the Sabbath since Old Testament times. Learning from both leads to a more solid understanding of many Biblical customs, and the Sabbath is one of them.

What does a Jewish Sabbath look like?

They observe the Sabbath on Saturday.

When God commands that the Sabbath should occur on the seventh day, the Jews take Him at His word and keep the Sabbath to the seventh day of the week, Saturday. Jewish days start around sundown, so the Sabbath is from Friday evening to Saturday evening.

They rest.

They take the command not to work as a declaration of their freedom from slavery, as slaves don’t usually get days off. When God freed them from slavery to the Egyptians, he took them as His people, establishing His covenant with them. The sign of this covenant is the Sabbath (Ex. 31:16 and Lev. 24:8).

They attend synagogue services.

They attend services as a family on either Friday evening or Saturday morning, or both.

They study God’s word.

The Torah is read during Friday evening and Saturday morning services. Orthodox Jews also study Torah as a family on Friday evenings and Saturday afternoons.

They spend time with family.

The Sabbath is a leisurely affair, with taking walks, playing games, and hanging out together making up much of the day. They have meals together, with blessings for the food, the Sabbath, and each other.

There’s a definite beginning and end.

They light two candles when it begins, indicating that the family should remember and observe the Sabbath. A small ceremony called Havdalah marks its end, separating it from the other days of the week.

What the Sabbath Looks Like at My House

My family has adopted many of these customs to our Sabbath. When we first began, it wasn’t easy to implement. Not working on Saturdays was difficult, but once I figured it out, having a day of free time was a welcome change! We gradually changed our focus to fill our Sabbath with bible study, family time, and rest.

Keeping the Sabbath has been such a blessing to my family. Our culture is nonstop. While this allows us to be very productive, many American Christians struggle to find time for what they claim are the most important aspects of their lives—their family and faith. True Sabbath observation helps properly align our priorities. When done correctly, the Sabbath becomes a day in one’s schedule where the top priorities stay on top—every week, every year, for generations.

Here are a few things my family does on the Sabbath:

- Bible study (individual and as a family)

- Attend synagogue

- Watch live streams from Beth Yeshua International or Founded in Truth Ministries

- Have special meals together

- Light candles to mark the beginning of the Sabbath

- Say specific blessings like this one, this one, and this one, which is my favorite!

- Eat challah bread

- Take naps

- Sleep in

- Hike or take a walk in nature

- Go swimming

- Eat simple snacks and meals that we prepared in advance

- Have a family outing, such as going to the zoo or botanical gardens

- Wish each other and others a “Shabbat Shalom!” or peaceful Sabbath

Our Friday evenings are getting more organized as Sabbath observation becomes routine. Each family member has specific roles on the Sabbath and looks forward to participating.

Shabbat Prep

Although we have activities and school that day, Friday is Preparation Day. We spend most of the day preparing for the Sabbath (Shabbat in Hebrew), the day’s focus. Without Preparation Day, preparing everything for a peaceful Sabbath is tough.

Each child (over 5) receives a Shabbat Prep Checklist on Friday morning. Their schoolwork, daily activities, and the chores they’re responsible for are on it. They have chores such as cleaning their rooms, selecting clothes for the next day, showering, and cleaning bathrooms. Doing these things on Friday allows for an evening and the following day, free to relax and enjoy family time.

My Shabbat Prep Checklist includes making meals for that evening and the next day, making challah bread, laying out clothing for the younger children and myself, cleaning the house, finishing laundry, and other tasks. I also ensure the table is set for our Sabbath meal and the necessary items are out (candles, candleholders, challah cover, decorative platters, etc.).

Here are the type of candles we usually use and a pretty cover for the challah bread similar to the one below.

Welcoming the Sabbath

We light our Sabbath candles and say blessings around dinnertime. Usually, this is done just after sunset at the start of the Sabbath, a job commonly reserved for the woman of the house. My oldest daughter says the prayer after I light the candles. She covers her head with a headscarf to say the blessing, which is a sign of respect for God.

Click here for a Step-by-Step guide to welcoming the Sabbath!

After the blessing over the candles, my husband blesses the children and me. The blessings are our favorite part of the Sabbath! My kids wait expectantly for their turn to be blessed. It’s touching when my husband says Proverbs 31, a blessing over me. There’s so much value in my kids watching him do this week after week! You can find out more about the blessings here and here.

After this, my husband says a prayer, and we eat. My husband usually has a subject to discuss related to the Sabbath, that week’s parsha, or just life in general. I try to choose a family favorite for the Friday evening meal to avoid any struggles over the little ones eating their dinner! Afterward, we always watch a movie as a family, complete with popcorn.

During the Day

On Saturday mornings, we either attend our Messianic Jewish Synagogue or do something recreational as a family. Saturday mornings are usually slower than mornings of other days, allowing time for bible study and rest. The Sabbath afternoon is often more leisurely than others, with naps and more study time being common activities.

We have an evening meal, then clean up after our restful day. We even include a Havdalah ceremony to mark the end of our Sabbaths.

Although our Sabbaths are free of work, we have plenty to do on Saturdays – the most important things! With the week’s work out of the way, we fill the day with much-needed rest, study of God’s word, and family time. What used to be an extra workday or a day to catch up on chores and household projects has become our most treasured day of the week. The best part is that keeping the Sabbath shows we’re in a covenant with the God of the universe, and we’re His people! What a marvelous blessing!